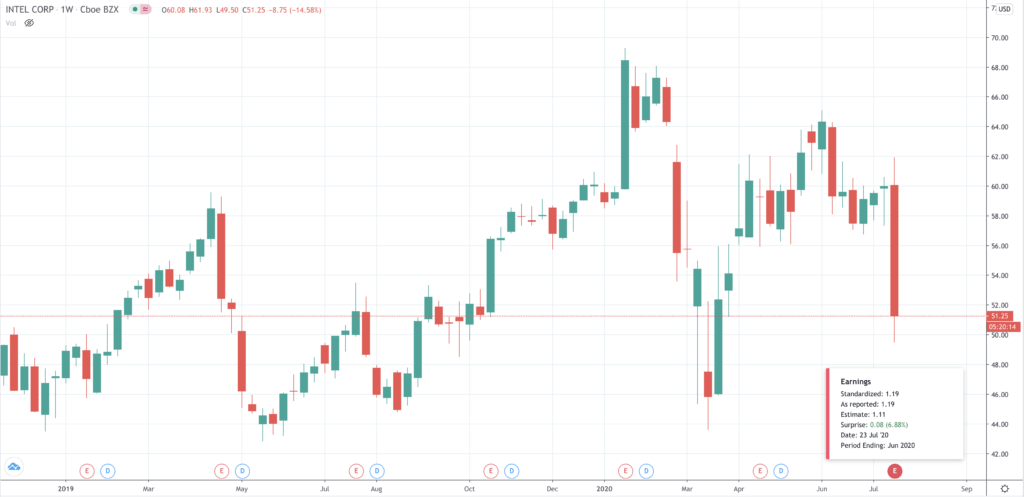

US chipmaker Intel shares have collapsed 15% at the time of writing to $50.8, as investors react with alarm to news of delays to its next generation of microprocessors.

Although the company reported earnings that beat analyst forecasts, it wasn’t enough to stop sellers coming out in droves.

Quarterly revenue was up nearly 20% at $19.7 billion on the back of demand from vendors of cloud services, as remote working took off during the lockdown.

In what should also have been encouraging news for shareholders, Intel reinstated guidance for the second half, with a healthy $75 billion revenue forecast.

This follows the ripping up of guidance previously as many companies did in response to the unknowns and uncertainty brought about by the pandemic.

Intel fabrication mess hints at deeper problem

But all of that paled into relative insignificance when the chipmaker revealed that its next-gen 7 nanometre chips would be delayed by at least six months.

This comes after the manufacturing stumbles already encountered with its 10 nanometre designs and fabrication, which has allowed Taiwian chipmaking giant TSMC to ease ahead in manufacturing prowess.

The latest hiccup has investors worrying that there may be something more fundamental to fret about at Intel, and that maybe the 10nm issues – and now 7nm – speak to a deeper problem.

At the centre of the angst is the notable difference in business models between TSMC and Intel and the direction of travel of the chip industry.

Intel is still far and away the largest of the chipmakers and it still commands the majority of profits made by the industry, but is its way of doing business increasingly an anachronism?

Intel is a vertically integrated company that both designs and makes its chips.

However, competitor TSMC makes chips to order that are designed by others. It seems to have developed more flexible and robust manufacturing processes, as it proves itself adept at meeting the manufacturing needs of different types of chip design.

Slow to grasp the importance of AI

Intel is still dominant in the manufacture of chips for PCs, however, but in other fast-growing areas, that’s not the situation.

Chips geared for the specific computational needs of artificial intelligence (AI), to perform machine-learning tasks, for example, or natural-language processing, has seen the likes of Nvidia moving ahead.

Graphical Processing Units (GPUs) – specialised chips that do what they say on the tin and are dedicated to running graphics in both consoles and PCs, have proven to be suitable for machine-learning. Intel, despite acquisitions in the area, has been slow to keep up.

Another fast-growing sector is computationally-intensive video rendering, again where Intel has proven a sluggish competitor.

And this is before we get started on the chips inside smartphone’s, where ARM’s (owned by Softbank) low-power chip designs are dominant.

Indeed it was in designing and manufacturing for smartphones that the split – between design on the one hand and the foundry fabricators on the other – first arose, and has now become the preferred approach for that part of int industry.

Looking at this landscape then, has provided shareholders with much food for thought – and many reasons to be vexatious and impatient with Intels execution slips.

Bernstein analyst Stacy Rasgon has downgraded the stock to under-perform: “From here we see things growing increasingly painful as 7nm delays are likely to overshadow anything good they can put forth, while magnifying any negative events, all while they fight an existential conflict with themselves as they attempt to figure a way out of the hole they have dug.”

Panic selling a signal for contrarians to buy Intel?

However, writing off Intel would be foolish.

Selling the stock as you drop it into the “legacy company” bucket is likely a serious misreading of where things really stand on wider view.

Think about what Apple is doing. Sure, it isn’t making its chips but it is designing some of them.

That gives it more control and arguably helps it to deliver performance gains because of its greater control over integration of all the moving parts that go into an iPhone, and also its desktop and laptop computers as it lets Intel go.

In other words, there are advantages that follow from being a vertical that Intel can still leverage. Certainly, it needs to overcome whatever institutional friction might be responsible for the missteps at the shopfloor level.

But just as the South East Asia manufacturers lent on American expertise to get their chipmakers off the ground in the first place, Intel will probably not be proud about helping that information and know-how reverse if required.

As mentioned, Intel has shown itself not to be averse to an acquisition or two to plug whatever gaps it must, seen in the purchase of Nervana and Habana.

And let’s not forget that although Nvidia, AMD and TSMC may have been growing faster over the past few years, Intel has still be growing, even if its valuation lags those of smaller competitors.

Intel profit of $21 billion in 2019 was more than the combined total of profits made by Nvidia, AMD and TSMC by 40%.

Intel has plenty have fight in it yet, which means that this pullback looks decidedly overdone.

Question & Answers (0)