Electric scooters (escooter) have finally been given the green light by the UK government and that could be just the sort of enticement UK investors are looking for.

Originally planning to rollout a regulatory framework for the vehicles in 2021, the government plans were brought forward in the light of the Covid pandemic.

On 4 July escooter companies were able to start trials in the UK.

The UK has lagged the rest of the world up until now because micromobility e-scooters were effectively banned. UK law treated escooters as motor vehicles, which aside from the ban itself, made their operation prohibitively expensive.

However, it has always been legal to use e-scooters on private land. As such, US startup Bird has exploited this loophole to get a head start with its scooter-sharing operation already up and running in the Olympic Park area of east London.

Below BuyShares takes an in-depth dive into the sector and what investors need to look out for and how to get a piece of the action, if you so desire.

Market leadership in escooters and valuations

Market leaders in Europe are split between US-based outfits such as Lime and Bird and home grown operations, with Sweden’s Voi arguably one of the best-established.

Other European startups making waves include Dutch firms Felyx (more below) and Step Mobility and Germany’s Wind Mobility.

Outside of the US and Europe, it is Asia that has been leading the way. Singapore micromobility hotshots include Beam, which raised $26 million in May this year for a total raise of $32.4 million.

Teleport was the first-mover in Singapore e-scooter-sharing, rolling out its vehicles back in June 2017.

Three and half-year-old Neuron Mobility claims to be the fastest-growing firm in the Asia Pacific region and also hails from Singapore. It completed its Series A funding round in December last year, pulling in $23.5 million. Beyond it home market, it has a footprint in Australia, New Zealand, Thailand and Malaysia.

US startups out in front, but burning cash

However, the largest firms are all American, at least as far as fundraising goes. Bird has raised around $700 million and its latest Series D gave it a valuation of $2.5 billion in October last year.

The US is the largest market, followed by Europe and then South Asia.

Bird’s main competitor, Lime (officially known as LimeBike – a trading name of Neutron Holdings) was on a similar valuation, as at February 2019.

But that was then. Those valuations have come down after much of the hype around the sector’s prospects dissipated in light of the sobering reality of the accelerating cash-burn both Lime and Bird were seeing.

For instance, by spring 2019 Bird was thought to be down to its last $100 million. Losses have been mounting, losing $100 million Q1 2019.

Not surprisingly then, the sector has undergone rapid consolidation since last year, with a frenzy of mergers and acquisitions, that, for example, witnessed Bird pounce on European outfit Circ in the latest such deal.

Consolidation had to come in a market that was not just burning cash as company’s sought to scale up, but also because it was flooded with operators offering products with little differentiation.

So it is not going to be all plain sailing – or riding – for the escooter startups, as they tout their visions of a greener, cleaner, less costly and congested world.

Lessons from the bike-sharing graveyard

For clues as to the near-term prospects of the nascent industry, look no further than the arena of the human-powered bikes and their electric variants.

As far as bikes go, the promise didn’t match reality and the graveyard of bicycles that have sprung up in China underline the extent of the failures, perhaps most notably in the fall from grace of Ofo.

To be clear, cycle-sharer Ofo hasn’t folded yet, but it has been forced to pivot towards e-commerce as its core sharing business hits the buffers.

Ofo ran into financial problems in 2018 because of the capital-intensive nature of the bike-sharing business.

As we have seen with the US e-scooter startups, achieving rapid scale comes at a high cost.

Each pedal bike set Ofo back $100 and were expected to last two years. Unfortunately for Ofo many of the bikes lasted as little as a month or two before falling into disrepair or prey to vandals.

There are lessons here for the escooter startups.

Solving the unit economics problem

To succeed, those companies seeking to make a go of the new opportunities opening in the UK and to beat off the competition in Asia, the US and continental Europe, need to get the unit economics right.

Instead of shelling out $100 for a bike, the escooter sharers are putting up more like $500 a unit for their fleets. With that kind of outlay, it easy to see how costs can mount up for proportionately small revenues.

Looking at Bird’s financials, it is reported to have taken in a miserly $15 million in revenue in the 2019 first quarter in which it lost $100 million. Venture capitalists have deep pockets but even they start to wince at such ratios.

So when we start to sift the wheat from the chaff, top of the tests we should apply will be a business model that bears down on fleet rollout and maintenance costs.

Regulatory hurdles

The other major problem facing the industry is regulation, which touches on a related matter, namely infrastructure.

Because the UK is something of backwater as far as escooter sharing goes, UK readers may have missed it, but in Berlin, Singapore and elsewhere the presence of the scooters approaches the same levels of ubiquity as the machines of the bike-sharers in the UK, and not in a good way.

With competing companies littering the streets, city authorities starting to pay attention. Even more so when pedestrians started getting injured in increasing numbers – and killed in the case of one old woman in Singapore – after collision with an escooter.

On the 5th November last year, with no warning, Singapore banned e-scooters from footpaths citing public safety issues.

At the time Neuron Mobility mobility complained that the new rules would put it out of business in the City state. Chief executive Zachary Wang said it was “legally not possible for us to run any business in Singapore.”

Singapore competitor and escooter pioneer Telepod said that the delivery business it had diversified into was in danger as it halted the start of its delivery service with partner Foodpanda.

“Because of these new rules, the delivery companies have to think of another transportation mode for all the delivery-men,” said chief marketing officer Chan Jit Yen.

Similar restrictions were introduced in Germany and elsewhere in response to what some politicians saw as a plague of e-scooters and a safety hazard.

Lack of suitable infrastructure means these bans play out differently depending on the environment. In places such as Germany and the Netherlands, which have well-developed cycle path systems, the impact is not as problematic.

Where e-scooter users are inclined to hog the pedestrian walkways because of lack of suitable alternatives, then the operators have much more of a problem.

In Singapore e-scooters were also banned from the roads.

The UK government is encouraging local authorities to make their built environment more cycle-friendly, so this should help e-scooter take-up when the startups finish their trials. However painting lines in existing roads is not quite the same as the purpose-built cycleways that exist in the Netherlands and elsewhere in continental Europe.

OK, those are the main hurdles the industry faces. Let’s remind ourselves about the opportunity.

$1.4 trillion addressable market

In little more than three years, the shared scooter and bikes sector has attracted 500 million users.

And the overall market for mobility-as-a-service (which includes ride-sharing, e-hailing and car-sharing in addition to escooter and bike sharing) could be worth $9.5 trillion by 2035.

Global bike-sharing is estimated to be €7.5 billion by 2021.

By other estimates the US micromobility addressable market could be worth an admittedly doubtful $1.4 trillion annually.

Singapore alone has around 100,000 owners of escooters, not counting those used by commercial operators and the sharing startups we are focusing on here.

Covid the trend accelerator

Moving on, let’s look at the impact of the Covid pandemic on mobility and the refashioning of city transit systems and private vehicle road usage.

Initially escooter firms shut down in may countries but as the lockdown lifts the pandemic may have accelerated a shift to micromobility.

If initial trends hold out, as gleaned from Apple and Google geo data, car use is rebounding faster than public transit.

With social distancing likely to be a feature of our lives for much longer than any of us would like, observing such strictures is easier in a car than on a train, bus or underground train.

But there is another way of getting about that is also social-distancing friendly and that is the bike and the e-scooter.

Obviously sharing poses problems in terms of viral infection, so providing gloves in addition to the already necessary helmets is going to be de rigueur.

In addition, assuming the electricity generation they depend on is from renewable sources and there is a dense-enough network of charging ports, electric scooters are definitely on curve too with climate change in mind.

In as far as they help shift people from carbon-polluting transportation and polluters, the startup purveyors of the micro mobility revolution can also make a pitch for favoured treatment from city governments, assuming safety issues are addressed in the package.

How investors can gain exposure to the e-scooter story

The only way to directly buy e-scooter shares is to be a venture capitalist or other institutional entity. Retail investors only way in for investing in startups is through a collective vehicle such as a unit trust (mutual fund) or a closed-ended (set number of shares) investment company vehicle.

UK investment companies (known as trusts) trade on the stock market like any other stock, while unit trusts have an open-ended structure, meaning the fund can grow by issuing more units of the fund to investors.

Scottish Mortgage trust is worth taking a look at as it is increasing the number of unquoted companies it invests in and has a strong tech bias.

But the most accessible way to play the sector might be to invest in a manufacturer of the e-scooters.

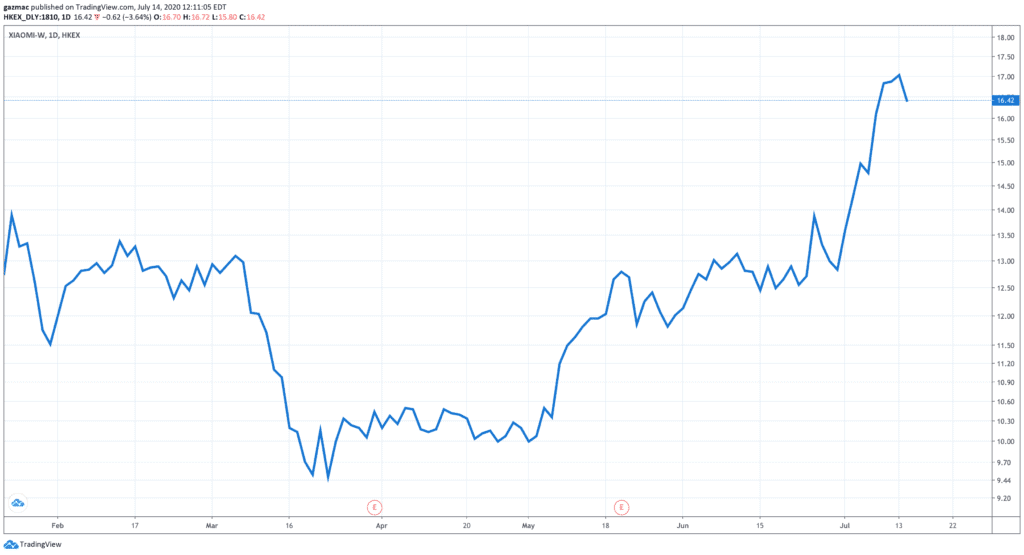

Xiaomi worth a look

Manufacturers include Xiaomi, the Chinese phone maker, and another China-based firm firm Ninebot (which bought self-balancing scooter pioneer Segway). Germany’s Unu is a key manufacturer in Europe. However, all those companies are private except Xiaomi.

The Xiaomi Mi M365 electric scooter priced around the competitive £500 mark is apparently selling well to consumers and could become a fleet favourite.

Once known as the Chinese Apple, the Xiaomi is known for its quality at a good price products, and this author saw its e-scooters making an appearance around London before the lockdown took hold.

Other big tech names looking at developing products in the sector are Alibaba. It recently partnered with BMW to research internet-plus vehicle tech, smart connectivity, AI and autonomous-driving, with micro mobility reportedly high up the agenda. This builds on a relationship the two companies had previously established.

As far as the startups go, Felyx should be on the radar even if you can’t buy shares in the company just yet.

The Dutch company has an interesting model which involves leasing, and could be one way to simultaneously reduce costs and extend the life of fleet units. This approach may help it to solve the unit economics problem we highlighted above.

Helbiz – founded by Italian Salvatore Palella – is planning an IPO with a dual listing on both Italia AIM and Nasdaq.

Palella brought e-scooters to Italy so knows the sector well and the company has officers in Singapore, Madrid, Milan, New York, Belgrade and in its home market. However, prospective IPO investors might be put off by a lawsuit brought by investors against the company around its venture in blockchain technology and the related coin offering.

Question & Answers (0)